Figurer på trummembran

Rumpukuviot

Sikäli kuin tiedetään, uralilaisista kansoista ainoastaan saamelaiset ovat maalanneet kuvioita shamaanirumpujensa kalvopinnoille. Keski- ja Itä-Siperian altailaisilla kansoilla kuviomaalattuja rumpuja taas esiintyy mutta niissäkin kuvitus vain harvoin yltää siihen rikkauteen, jota saamelaisissa rummuissa yleisesti tavataan.

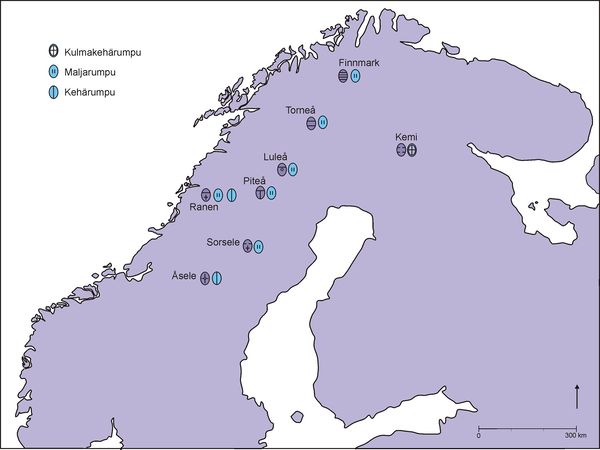

Kuvituksensa puolesta rummut on tutkimuskirjallisuudessa jaettu kahdeksaan tyyppiin, mutta nämä palautuvat kuitenkin viime kädessä kahteen perusratkaisuun, aurinkokeskiseen ja segmenttijakoiseen. Eteläisissä ns. Åselen tyypin rummuissa täysin aurinkokeskinen jäsentely keskeiskuviona juuri auringoksi tulkittu rombi, josta lähtee neljä sädettä; muut kuviot kiertävät rumpukalvon kehää tai sijoittuvat rombin ja kehäkuvioitten välialueelle. Ruijan, Tornion ja Kemin tyypeissä tavataan selkein segmenttijaotus; Ruijan typissä kalvo jakautuu viiteen, Tornion ja Kemin rummuissa taas kolmeen segmenttiin. Kemin rummuissa on lisäksi aukot segmenttien välillä. Lisäksi tunnetaan sekatyyppisiä rumpuja, joissa aurinko on joko rombina tai pyöreänä kuviona keskellä ja rummun yläosaan on erotettu yksi segmentti ja myös rumpuja, joissa yläsegmentistä lähtee rummun alaosaan asti ulottuva pystyviiva (Piitimen tyyppi). Pystyviivan on ajateltu mahdollisesti viittaavan maailmanjärjestystä ylläpitävään maailmanpatsaaseen (taivaanjumala). Karkeasti ottaen tyypillisimmät aurinkokeskiset rummut (rombikuvio ja ei segmenttijakoa) ovat peräisin etelästä ja lännestä kun taas selkeimmin segmenttijakoisia rumpuja on tavattu pohjoisessa ja idässä. Valitettavasti koltta- ja kuolansaamelaisten alueelta ei tunneta yhtään rumpua. Ruotsalainen Ernst Manker on inventoinut kaikki säilyneet runsaat 70 noitarumpua niin tekotavan, rumpukuvioitten kuin käytettävissä olleitten taustatietojen osalta (1938, 1950).

Rumpukuvioitten tulkitseminen on erittäin vaikeaa ja vanhemmassa tutkimuskirjallisuudessa esiintyy todennäköisesti runsaasti ylitulkintaa ja perusteettomia johtopäätöksiä; myös Mankerin tulkintoihin (1950) on syytä suhtautua kriittisesti. Jo maailmakuvan rakenneta koskevien johtopäätösten vetäminen rumpujenkalvojen yleishahmotuksesta on vaikeaa puhumattakaan yksittäisten rumpukuvioitten tulkinnasta. Erityisen ongelman muodostaa se, että käytettävissä on vain vähän rumpujen alkuperäisten käyttäjien kuvioista tekemiä selvityksiä, ja nekin on yleensä annettu lähdekriittisesti epäilyttävissä tilanteissa eli oikeudenkäyntien yhteydessä tai pelätylle auktoriteetille, papille. Osa rumpukuvioista on suhteellisen naturalistisia, kuten poro, karhu tai käärme, tai muuten helposti tunnistettavia (esim. noaidi rumpuineen), kun taas jotkut kuvioista ovat hyvin pelkistettyjä tarjoamatta mitään nykytulkitsijalle avautuvia piirteitä.

On oletettu, että aurinkokeskisiksi tulkittuja rumpukalvoja olisi luettu rummun yläosaan sijoitetusta Taivaanjumalasta alkaen vastapäivään siten, että vainajala (kuolema ja vainajat) ja maailman pimeän puolen hallitsija Ruto sijoittuisivat taivaanjumalasta lähes täyden kierroksen päähän jälleen lähelle rummun yläosaa mutta siis vastapäivään lukemisen kannalta mahdollisimman kauas siitä. Ihmisten arkiseen elämään liittyvät aiheet, kuten porokaarre, sijoittuvat välialueelle kuten myös maanpäälliset jumaluudet. Segmenttijakoisista rummuista on taas perinteisesti ajateltu niiden heijastavan kolmikerroksista maailmanhahmotusta: ylinen (taivaanjumalan ja muiden taivaallisten jumaluuksien) maailma, keskinen (ihmisten ja maanpäällisten jumalien) maailma ja alinen, vainajien ja maanalisten jumaluuksien maailma. Tämä liittyy samanistiseen maailmankuvaan ja rumpu olisi tällöin muodostanut noaidin kognitiivisen kartan tuonpuoleisiin; Kemin tyypin rummussa segmenttien eli maailmantasojen välillä on jopa nähty kulkuaukot samaanille (samanismi). Yhdessä rummussa voidaan nähdä noaidi apuhenkensä, käärmeen, hahmossa ryömimässä sisään maailmantasojen välisestä aukosta aliseen maailmaan. On arveltu, että segmenttijakoinen rumpu olisi aurinkokeskiseen nähden arkaaisempi ja edustaisi saamelaiskulttuurissa sen itäistä lähtökohtaa, sen uralilaista taustaa. Samaan saattaisi viitata se, että kristillisten vaikutteitten määrä on aurinkokeskisten rumpujen kuvioissa varsin suuri (esim. taivaanjumalan persoonien sädekehät), kun taas säilyneistä kahdesta keminsaamelaisesta rummusta ne näyttävät jokseenkin puuttuvan.

On mahdollista, että rumpujen kuviointi on vähitellen kehittynyt varhaiskeskiajalta alkaen rikkaammaksi. Tähän viittaa se, että vanhimmassa saamelaista shamaani-istuntoa kuvaavassa dokumentissa, 1100-luvun lopulta olevassa Historia Norwegiaessa rumpukuvituksen mainitaan ainoastaan valaat, poro valjaineen, sukset ja vene airoineen, ja itse asiassa nämä olivat rummun kalvolla olevia metallifiguureja. Nämä on tulkittu noaidin sielunmatkallaan tarvitsemiksi kulkuvälineiksi tai hänen apuhengekseen (valas). Shamanointia ajatellen rumpukuvioinnin ei liene tarvinnut olla rikkaampi. Näin onkin myös arveltu, että rumpukuviointi olisi vähitellen kehittynyt monimuotoisemmaksi, kun rumpua alettiin käyttää myös ennustamiseen (esim. karhunpalvonta) oletuksen mukaan siis myöhemmin kuin samanoimiseen (trumman). On mahdollista, että tämä edustaa lännestä päin tullutta, naapurikansoilta omaksuttua ei-uralilaista innovaatiota. Säilyneissä rummuissa kuvioinnin rikkaus vaihtelee suuresti; osa on hyvinkin vähäkuvioisia.

Yksittäisistä rumpukuvioista on annettu lisää esimerkkejä niiden jumaluuksien kohdalla, joihin kuvioiden on oletettu viittaavan (taivaanjumala, tuulimies, Ailekis olmak, áhkka-jumalattaret, Ruto).

Meavrresgárri, the shaman drum

Shaman drum: markings

Shaman drum: markings. As far as we know, of the Uralic peoples it is only among the Saami that markings were painted on the skins of the shamans drums. There are painted patterns on the drums of the Altaic peoples of central and eastern Siberia, but rarely do they exhibit the richness that is to be found on the Saami drums.

On the basis of their markings, the Saami drums have been divided into eight types, but these ultimately derive from two basic patterns: one heliocentric and the other segmental. In the southern so-called Åsele drums, the heliocentric organization has in the centre a figure in the form of a rhomb with four projecting rays, and this has been interpreted as representing the sun. The other figures circle the edge of the skin or are situated between the rhomb and the encircling forms. The Finnmark, Tornio and Kemi types of drum represent most clearly a segmental arrangement; in the Finnmark drum, the skin is divided into five segments, and in the Tornio and Kemi drums into three. In the Kemi drums there are also gaps between the segments. There also exist combinations of both basic types in which in the centre there is a figure in the form of a rhomb or a circle and one segment (perhaps representing the sky) is separated off at the top of the drum skin, and also drums in which there is a vertical line running from the upper segment to the lower part of the drum (the Pite type). The vertical line has been interpreted as a symbol of the pillar of the world which maintains universal order (Radie). Generally speaking, the heliocentric drums (with a rhomb figure and no segments) are from the south, while the most clearly segmented drums were found in the north and east. Unfortunately no drums have been found in the Skolt Saami area or in the Kuola Peninsula. The Swedish ethnographer, Ernst Manker made an inventory of all the seventy surviving drums according to the method of their manufacture, their markings and any background information available about them: Die lappische Zaubertrommel I II (1938, 1950).

The interpretation of the drum markings is extremely difficult, and the older research literature is probably fraught with over-interpretation and unwarranted conclusions. Manker's interpretations (1950), too, should be regarded critically. It is extremely difficult to draw any conclusions regarding the cosmology of the Saami on the basis of the general disposition of the drum, let alone the interpretation of the patterns on individual drums. A particular problem is constituted by the fact that there exist only a few explanations of the markings by the original users of the drums, and they were given in conditions which cast doubts on their reliability as sources;often they were given in court trials or to feared authorities like priests. Some of the drum markings are relatively naturalistic figures like reindeers, bears or snakes or otherwise easily identifiable (for example a shaman, noaidi, with his drum), while others are highly abstract and offer no clues to modern interpreters.

It has been surmised that drums that have been interpreted as heliocentric were read from the Sky God (Radien) at the top of the drum anticlockwise round to the dead and Ruto, the ruler of the dark side of the world, who were also situated at the top but almost a full anticlockwise circle away from the Sky God. Elements connected with people s mundane life the reindeer corral are located in the intervening area, as are the earth gods. The segmental drums have traditionally been interpreted as reflecting a tripartite cosmology: an upper world of the Sky God and the other celestial divinities, a central one of man and the earth deities; and a lower world of the departed and the nether gods. This is connected with the shamanistic view of the world, and the drum would have been the shaman's cognitive guide to the other world. Drums of the Kemi type have even been thought to contain areas between the segments, i.e. levels of the universe, that represented passages along which the shaman could travel (Shamanism). On one drum, it is possible to discern the noaidi in the form of his animal assistant, the snake, crawling from an opening between the levels of the universe into the underworld. It has been argued that the segmental drum was older than the heliocentric one, and that it represented the eastern, Uralic origins of Saami culture. This might also be indicated by the fact that the amount of Christian influences in the marking on heliocentric drums (for example, the halo on the figures of the Sky God) is fairly high, while they would seem to be missing from the two surviving Kemi drums. it is possible that the markings of the drumskins gradually became more elaborate from the Middle Ages on. This is indicated by the fact that in the oldest document that describes a shamanistic séance, the eleventh-century → Historia Norvegiae, the markings on the drum are mentioned as containing only figures representing whales, a harnessed reindeer, skis and a boat with oars, and even these were metal figures on the skin of the drum. They have been interpreted as being means of transport for the shaman on his journeys or as his spiritual assistants (the whales). For the purposes of shamanistic activity, probably the patterning did not need to be any more elaborate. This is also the basis of the reasoning that the markings gradually became richer when the drum began to be used for divination (for example Bear cult), which is estimated to have come later than shamanism. It is possible that this represented a non-Uralic innovation borrowed from neighbouring peoples in the west. The richness of the markings on the surviving drum skins varies considerably; some have very few figures on them.

Further examples of individual drum figures are given in the entries for those gods that they are believed to refer to (Sky God/Radien, Bieggaolmmái, Ailekis olmak, Áhkka goddesses and Ruto.