Kuolema ja vainajat

Kuolema ja vainajat

Vaikka ihmisen elinikä katsottiin periaatteessa ennalta määrätyksi, kuoleman enteitä saamelaiset kuitenkin ottivat monista asioista, ja monet asiat myös saattoivat vaikuttaa elämän pituuteen. Seulasten eli Plejadien tähtikuviosta sanottiin, että kun "syksyllä ensi kerran näkee Seulaset, voi niistä päätellä elämänsä pituuden. 20 vuotta on perusikä, ja jokaista selvästi näkyvä Seulasten tähteä kohti lisätään tähän 10 vuotta. Jos kaikki tähdet näkyvät kirkkaina, on katsojan ikä 90 vuotta". Monet tapakulttuuriin liittyvät tai ahneudesta, turhamaisuudesta varoittavat tabusäännöt oli sanktioitu kuoleman uhkalla: "ei saa mitata pituuttaan; siinä ottaa ruumisarkkunsa mittoja". Pian tapahtuvaa kuolemaa ennakoivat varsinkin eräät linnut (enne-eläimet) ja erityisesti oudolla, usein liian helpolla tavalla saatu tai kohtuuttoman runsas saalis. Tästä käytettiin nimitystä mieðus, suom.marras. Saamelaisessa mielenmaisemassa elämän ei kuulunut olla liian helppoa.

Saamelaiset ovat esikristillisenä aikana haudanneet kuolleensa aina niille sijoille, tai ainakin sen paikan lähelle, missä kuolema oli sattunut tapahtunut. Kalmistoja ei rakennettu, mihin syynä oli yhtäältä liikkuva elämäntapa ja toisaalta vainajia kohtaan koettu pelko. Viimeksi mainittu on tyypillinen eräkulttuuriin liittyvä piirre. Juuri kuolinpaikalle oli tapana pystyttää esim. vainajan käymäsauva muistomerkiksi, myöhemmin yleensä risti. Esihistorialliset haudat viittaavat siihen, että saamelaiset alun perin ovat haudanneet kuolleensa yleisarktiseen tapaan maan päälle, yleensä kallionkoloon. Jos ei kalliokoloa ollut käytettävissä, hauta saatettiin rakentaa maan päälle ja peittää laattakivillä. Mikäli kuoppa tehtiin, se oli hyvin matala, muutaman kymmenen sentin syvyinen, ja se peitettiin ohuella maa- tai turvekerroksella. Tällainen oli lähes pintahautaus. Varsin yleinen oli tapa haudata vainaja ahkioonsa. Koloon tai pintamaahan hautaaminen oli varmasti osin käytännön sanelema asia, mutta on saatettu myös ajatella, että vainajasielu näin helpommin pääsee siirtymään vainajalaan. Kaikkiaan tavat näyttävät vaihdelleen luonnonolojen ja vuodenaikojen mukaan, joten asiaan lienee suhtauduttu varsin käytännöllisesti. Hautaussuunnasta ei ole havaittu mitään selkeää sääntöä.

Kristillisenä aikana tuli tavaksi haudata väliaikaisesti saariin, jos vainaja oli kuollut kesällä, ja vasta hankikelillä viedä kirkkomaahan. Yleismaailmallinen ajatus on, että vesi, varsinkin virtaava vesi, on este tai ainakin hidaste vainajahengille. Väliaikaishautaus tehtiin joko turpeen alle tai vainaja ripustettiin ahkiossaan puuhun tai pantiin telineelle. Tärkeintä oli pitää ruumis turvassa petoeläimiltä, jotka voisivat hajottaa luurangon ja tuhota siinä asuvan elämänprinsiipin (sielu). Saamelaiset pelkäsivätkin erityisesti sellaista kuolemaa, jossa ruumis kokonaan tuhoutui tai joutui kadoksiin, kuten hukkuminen tai petojen raatelemaksi joutuminen. Vainajan itsensä kannalta tämä merkitsi sitä, ettei hän enää voinut saada vainajalassa itselleen uutta ruumista, eikä siten elää haudantakaista elämää. Jälkeenjääneille se merkitsi epävarmuutta vainajan olinpaikasta ja siten kummittelun mahdollisuutta. Onnettomuuteen joutuminen oli kriittistä jo sinänsä, koska kuolema saattoi näin olla ennenaikainen (sielu) ja jo siten johtaa kummitteluun. Rumpukuvioista ja noidan (noaidi) vainajalanmatkaa koskevista kuvauksista päätellen saamelainen vainajala, Jábmiidáibmu, sijaitsi jossakin alhaalla ja kaukana. Valtaa siellä piti naispuolinen jumaluus, Jábmiidáhkka. Kysymyksessä näyttää olleen metsästyskulttuureille tyypillinen etävainajala. Vainajalan paikka oli segmenttijakoisissa rummuissa rummun alaosassa ja aurinkokeskisissä rummuissa liki täyden kierroksen päässä Radienista ja muista taivaanjumalista. Lähimpänä sitä oli Ruto. Noidan sielunmatkan kuvaukset puolestaan korostavat vainajalan matkan pituutta ja vaivalloisuutta. Mikäli sáivalla oletetaan olevan yhteys varhaisimpiin saamelaisin vainajalakäsityksiin, on Jábmiidáibmun mahdollisesti alunperin kuviteltu sijainneen veden alla. Tulkintaa tukee myös Historia Norvegiaen shamaani-istuntoa koskeva kuvaus, jossa matka vainajalaan tapahtuu sukeltamalla, sekä ylipäätään se, että noidan apuhenki alisilla (vainajalan) matkoilla oli kala. Vainajalassa vietettiin enemmän tai vähemmän hyvää, maanpäällistä elämää muistuttavaa elämää. Tästä kertovat hauta-antimet, jotka yleensä olivat arkisia tarve-esineitä, kuten jousi ja nuolia, kirves ja tulentekovälineet. Vainaja sai kuoltuaan saman vallan ja arvoaseman kuin hänellä eläessäänkin oli ollut. Alisessa maailmassa kaikki on kuitenkin antipodista, eli ylösalaisin, nurin- tai toisinpäin. Erään noitarummun kalvolla nähdäänkin vainaja vaipumassa pää edellä vainajalaan.

Itäsaamelaisten parista on tavattu käsityksiä, joiden mukaan vainajala sijaitsi tähtitaivaalla, ja kolttasaamelaiset ovat uskoneet väkivaltaisen kuoleman saaneiden, "rautaan kuolleiden" siirtyvän revontuliin, joihin näiden haavoista vuotava veri aiheuttaa punaisen värin.

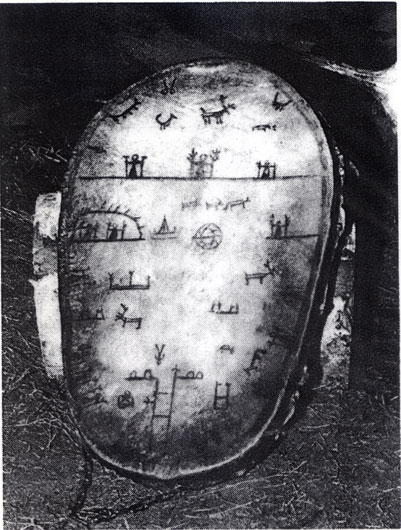

Noitarummuilla vainajala on tikapuumainen kuvio, mikä viitannee vainajalan osastoihin, tai kekomainen kuvio. Katolisena keskiaikana Jábmiidáibmu muodostui länsisaamelaisilla kiirastuliopin mukaiseksi välitilaksi, josta hyvin elänyt pääsi taivaanjumalan luokse Radienáibmuun ja huonosti elänyt puolestaan joutui Ruton isännöimään pimeään tuonelaan (Rotáibmu). Monien lähteiden mukaan kristillinen helvetti oli kuitenkin vielä erikseen. On kuitenkin mahdollista, että kehitys kohti jakautunutta vainajalaa on saamelaisilla ollut myös kulttuurinsisäinen piirre (sáiva).

Vaikka elämä vainajalassa muodosti varsin tarkoin paralleelin maanpäälliselle elämälle, oli jonkinlainen palkkio / rangaistus -ajattelu rakennettuna sisään arkaaiseenkin vainajalakäsitykseen. Se, miten hyväksi ihmisen elämä vainajalassa muodostui, riippui siitä miten hänestä oli eläessään joiuttu, ts. ihmisen maineesta. Jokainen pyrki siis elämään siten, että hänestä joiuttaisiin paljon ja hyvää. Toisaalta on tietoja siitä, että ihminen eli vainajalassa yksilönä vain niin kauan kuin hänet joiuttiin. Kun yksilöllinen muisto oli kalvennut, ei vainajalasta ollut enää mahdollisuutta "syntyä uudelleen" suvun lapsissa, ja vainaja muuttui osaksi vainajahenkien kollektiivista kasvotonta joukkoa.

Myöhäisperinteessä vainajiin liittyvät uskomukset ovat ilmenneet erityisesti vainajaolennon kohtaamisessa. Kohta kuoleman jälkeen, "sieluaikana", tämä oli odotuksenmukaista eikä sitä pelätty. Vainaja saattoi tällöin vielä ilmoittaa joistakin toivomistaan käytännön toimenpiteistä tai vaatia oikaisua tapahtuneisiin vääryyksiin.

Myöhäisperinteessä vainajien ja kaiken heihin liittyvän pelko on ollut suuri. Johan Turin mukaan jo pelkästä ruumiin hajusta saattoi saada kuolemantaudin. Kuten suomalaisillakin kuolemaan ja ruumiisiin liittyivät kuolleen "haltijat", jotka saattoivat paitsi tuottaa taudin,myös antaa "näkijän" lahjan:

"Jokaisella kuolijallakin on omat haltijansa ja kuolijan haltijat ne ovat mitkä siitä tarttuvat ihmiseen, kuolijan vaatteesta ja antavat sen näön" (Paulaharju, Muonio 1921). "Näkijä näkee rumia henkiä siinä paikassa missä väkivaltainen kuolema tapahtuu" (Paulaharju, Enontekiö 1922)

Odottamaton vainajan, erityisesti äpärän, kastamattomana surmatun lapsivainajan eáhparaš, kohtaaminen oli vaarallista. Se saattoi aiheuttaa tilan, josta käytettiin nimitystä ráimmahallan, pohjoisen suomeksi "raimaantuminen". Tilalle oli ominaista levottomuus, tuskaisuus ja voimattomuus ja se saattoi pahimmassa tapauksessa johtaa kuolemaan. Sitä on selitetty muistumaksi samanistisesta sairausselityksestä, sielunmenetyksestä: ihminen sairastuu, kun hänen yksilöllisyyttä kantava sieluosuutensa tai hänen hyvinvoinnistaan huolehtiva haltijansa poistuu. Usein vainajaolennon kohtaamiseen liittyy säikähtäminen, mutta jokin vainajiin liittyvä, esim. haudattu ruumis, saattoi aiheuttaa tilan myös uhrin tietämättä. Vainajien jäännösten ja kaiken heidän kanssaan tekemisissä olleen katsottiin kantavan mukanaan jotakin ihmisen sielullisesta olemassaolosta niin, että se saattoi ilmetä levottomuutena, kummitteluna, näkyinä yms.

Toinen kummitteleva vainajaolento oli merisaamelaisten tuntema rávga (< norj. draug, 'hukkunut'), Ruijan suomalaisten eli kveenien "meriraukka". Siihen liittyväperinne on saanut paljon norjalaisia vaikutteita. Rávga selitetään hukkuneeksi ihmiseksi. Se on siunaamaton ja siksi statukseton vainaja. Se kuvataan yleensä ihmistä muistuttavaksi pitkätukkaiseksi olennoksi. Tavallisesti rávga ei ahdistele ihmisiä, vaan ainoastaan huutamalla (usein matkimalla) häiritsee. Karkotuksena käytettiin hautauskaavan lukemista tai muuta siunausta.

Tietoisesti vainajiin liittyvää "väkeä" käytettiin hyväksi mustassa magiassa, mikä saamelaisten kohdalla usein tarkoitti ns. ruumiinmultien juottamista. Kuolleita saatettiin myös "nostattaa", toisinaan ihmissusien hahmossa. Myöhäisperinteessä myös stállu toisinaan on selitetty nostatetuksi vainajaksi. Mustaan magiaan liittyvä myöhäisperinne on luonteeltaan jo yleiseurooppalaista.

Sisällysluettelo: Muinaisusko, mytologia ja folklore

The death and the dead ones

There are numerous beliefs among the Saami attached to death and the dead, some of which go back to a pre-Christian view of the world, while others belong to the later Christian tradition. Although the Saami did not have any special fear of death, a long life and good health were sought-after blessings. The Inari Saami said that happiness was good health, for from it everything else would follow. On the one hand, the departed were experienced both as a threat, spirits who longed for their nearest ones (Shamanism) and as souls displaced because of a mysterious destructive → supernatural power that was connected with their earthly remains. On the other hand, for the Saami the dead also had the attributes of protective, beneficent spirits (sáiva).

The Saami experienced many things as portents of death, and many things were also felt to affect the length of one's life. It was said in the early twentieth century by the Inari Saami that when one saw the constellation of Pleides for the first time in the autumn it was possible to calculate the length of one's life. The basic age was twenty years, and one could add another ten years for every star of the Pleiades that was clearly visible. If one could see all the stars of the constellation shining bright, one would live to be ninety. Many taboos relating to customs or admonishing against greed or vanity were sanctioned with the threat of death; when reindeer milk was frozen, it was not permitted to count the levels of the milk because at the same time the counter would be tallying the number of her or his years to live. An immanent death was portended by numerous birds and particularly by a prey obtained in a strange, often too easy, way. The word used for this was mieđus (Animal omens).

During the pre-Christian period, the Saami always buried their dead in or around the place where the death had taken place. They had no burial grounds, which was a consequence both of their nomadic way of life and of the fear they had of the dead; this latter phenomenon was a typical feature of hunting cultures. It was a custom to plant the dead person's staff at the place of death in her or his memory; later the staff was generally replaced by a cross.

Pre-historical graves indicate that originally the Saami buried their dead according to the general Arctic practice above the ground, usually in a crevice in a rock. If no such hole could be found, they might make a burial mound above the ground and flag it with stones. If a grave was dug, it was very shallow, no more than a few dozen centimetres deep, and it was covered over with a thin layer of earth or turf. This procedure was almost the same as surface burial. A very common custom was to bury the dead person in his sledge. Interment in a rock crevice or in a shallow grave was certainly dictated by natural circumstances, but it may also have been thought that the soul of the departed might thereby more easily gain access to the world of the dead. Generally, the methods of burial seem to have varied according to the place and the time of the year, so it would appear that the Saami had a fairly pragmatic attitude towards burial. No particular rule appears to have governed the direction in which the body was buried.

During the Christian era, there was a period when it was the custom to bury dead people on islands if they died in the summer and only to take their bodies to the graveyard when the snow had an icy crust over it. It is a universal idea that water especially flowing water is a barrier, or at least an impediment, to the soul of a dead person. The body was buried temporarily under turf, or the departed person was hung in his sledge from a tree or placed on a rack. The most important thing was to keep the body safe from predatory animals, which might break up the skeleton and destroy the principle of life that resided therein (Soul). The Saami particularly feared a death in which the body was totally destroyed or lost, as in the case of a person drowning or being devoured by wild animals. For the departed, this meant that she or he could never again find a new body in the land of the dead nor live a life beyond the grave, but would remain a displaced soul. For the survivors it meant uncertainty about the whereabouts of the departed and consequently the threat of being haunted. An accident was critical if only because the death caused thereby might be a premature one (Soul), which could result in the victim becoming a ghost.

To judge from descriptions of the patterns on the shaman's drum and the journey of the shaman's soul to the land of the dead, the location of the Saami land of the dead (Jábmiidáibmu) was low and far away. According to western Saami sources, it was ruled over by a female divinity Jábmiidáhkka. It would seem to have been a distant land of the dead of the kind typical of hunting cultures. The world of the dead was located in segmentally patterned drums at the bottom end and in heliocentric drums almost a whole circle away from the Sky God. Closest to it was Ruto, the God of Pestilence. Descriptions of the journey of the shaman's soul's to the land of the dead emphasize how long and difficult it was. If it is assumed that the sáiva was connected with the earliest Saami conceptions of a world of the dead, Jábmiidáibmu was originally conceived of as being located under water. This interpretation is also supported by a description of a shaman's ritual in Historia Norvegiae, in which the journey to the land of the dead takes place by diving, and generally by the fact that the shaman's assistant in his journeys below was a fish.

Life in the land of the dead was more or less pleasant, resembling that on earth. This is evidenced by burial objects, which were usually ordinary everyday implements like bows and arrows, axes and fire-making equipment. After his death, the departed person would receive the same status and position that he held in life. In the nether world, however, everything was inverted, upside down or contrary. One shaman's drum skin shows a departed person sinking headfirst into the land of the dead. In the eastern Saami tradition, those who met with a violent death ( died of iron ) went to the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis), where the blood from their wounds created the colour red.

The symbol for the world of the dead on the shaman's drum resembled a ladder, which probably indicates a division into compartments, or it had a conical shape. During the Middle Ages, when the dominant religion was Roman Catholicism, for the western Saami Jábmiidáibmu became a temporary holding place like purgatory, from which a person who had led a good life passed to the Sky God Radienáibmu, while one whose life had been a bad one went to a dark underworld Rotáibmu ruled by Ruto. According to many sources, the Christian Hell was still a separate place. It is, however, also possible that the development into a divided world of the dead was internal to Saami culture (Sáiva).

Although there was a fairly strict parallel between life in the realm of the dead and that on earth, some kind of idea of reward and punishment was still intrinsic in the ancient conception of the world of the dead as well. How good a person's life was there depended on the chants (Chanting) that were made about him; in other words on his reputation and the way he had lived. Again, there is information that suggests that a person lived as an individual in the world of the dead only as long as chants were made about him. When the memory of them as individuals had faded, departed persons could no longer be reborn in the children of their clans, and they became part of the collective faceless mass of the spirits of the dead.

In the late tradition, beliefs about the dead found expression mainly in meetings with a dead person, particularly a displaced soul. Meeting a person who had died a natural death and been buried in the usual way soon after their death, in the so-called soul time was only to be expected and thus it was not feared. The departed person might even then express wishes to the living about things she or he wanted to be done or require that certain wrongs be righted. However, the fear of dead bodies was great. According to the writer Johan Turi, one might contract a fatal disease from the mere smell of a dead body. On the other hand, the genii of the dead who attended upon the death and the corpse might not only cause disease but also give a person who came into contact with them the gift of seeing the hereafter.

An unexpected meeting with a dead child (frequently an illegitimate one) who had been killed before baptism (eahpáraš) was considered to be dangerous; it might cause a condition called ráimmahallan, which was characterized by restlessness, anguish and listlessness, and which in the worst cases led to death. Usually a living person experienced fear on meeting a dead one, but a similar fright could also be caused without the knowledge of the departed by something connected with the dead for example, a corpse; the remains of dead persons and everything connected with them were thought to carry with them something of the spiritual existence of the departed, and this could result in restlessness, haunting, visions, and so on.

Another dead creature that haunted people was the rávga (< Norwegian draug drowned ), who was known among the maritime Saami. This tradition had a strong Norwegian influence. The rágva was a drowned person whose soul had not been blessed and was therefore without status. It is generally described as a long-haired creature resembling a human being. Usually the rágva did not bother humans except by calling out to them, often copying human cries. To drive it away, the burial service or some other prayer was recited.

The supernatural power that was associated with the dead was exploited in black magic, which for the Saami usually meant the procedure of using human remains in magic potions. The dead might also be raised in the form of werewolves. The later tradition of necromancy is pan-European in its character.