Pre-Christian gods

Esikristilliset jumalat

(J. Porsanger & R. Pulkkinen)

Esikristilliset jumalat voidaan segmenttijakoisten rumpujen vertikaalisen maailmankuvamallin mukaan jaotella taivaanylisiin, taivaallisiin, maanpäällisin ja maanalisiin. Tiedot saamelaisten vanhoista jumalista ovat epävarmoja, tulkinnanvaraisia ja suhteellisen myöhäisiä. Ne on kerätty vasta Lapin intensiivisimmän lähetysrynnäkön aikana 1600-1700 -luvuilla ja enimmäkseen Skandinavian puolella. Tässä vaiheessa vanhat saamelaiset jumalakäsitykset olivat jo hämärtyneet. Toisaalta skandinaaviset ja myös kristilliset vaikutteet olivat ehtineet suodattua jo varsinkin läntisten saamelaisten esikristilliseen maailmankuvaan. Toisaalta taas enimmäkseen vieraiden kielten (ei-saamen) avulla kerätyssä aineistossa on virhelähteensä. Tulkki tai saamelainen tiedonantaja itse saattoivat soveltaa saamelaisjumalien nimiä muinaisskandinaavisen mytologian mukaan tehdäkseen omat käsityksensä ymmärrettäviksi ulkopuolisille. Klassisten lähteitten laatijat, yleensä lähetyssaarnaajat, ovat jo vahvasti tulkinneet sitä mitä heille on kerrottu ja mitä heille on haluttu kertoa. Vanhimmat, elävän saamelaisen muinaisuskon aikaiset lähteet on yleensä muodostettu juuri lähetyssaarnaajien keräämän ja tulkitseman länsisaamelaisen materiaalin perusteella. On epäselvää, missä määrin olemassaolevat tiedot edustavat saamelaisten uskonnollisten spesialistien, noitien, tietoutta ja missä koko kansan käsityksiä, kollektiivitraditiota.

Taivaanyliseksi jumalaksi voidaan laskea taivaanjumala ja maailmanjärjestyksen ylläpitäjä, josta on tietoa läntisiltä saamelaisalueilta. Tästä on etelä- ja uumajansaamelaisalueilla käytetty (nimet ovat tässä vanhoissa lähteissä tavattavien muotojen mukaisesti) nimitystä Radien (myös Mailmen Radien, Maailman Radien) ja hieman pohjoisempana ja idempänä, nimittäin piitimen-, luulajan- ja Tornion alueen pohjoissaamessa,Veralden Olmai, Maailman mies (ruots. värld 'maailma') tai Veralden-Radien, Maailman Radien (Taivaanjumala), Raedie. Jo nimet osoittavat vahvaa skandinaavista vaikutusta. Kristillisten lainojen osuus tulee esiin siinä, että noitarummuilla Raedie kuvataan kolminaisuutena.

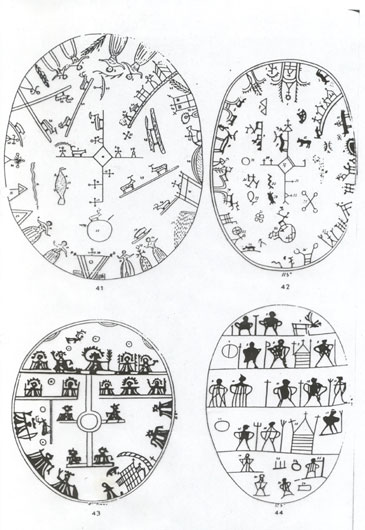

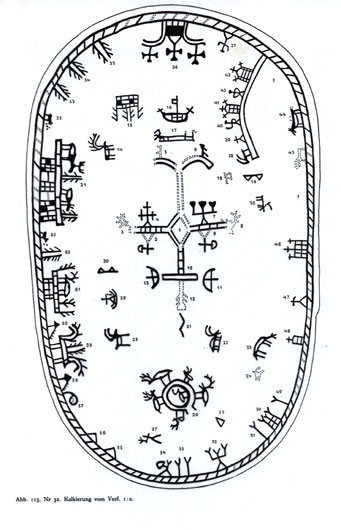

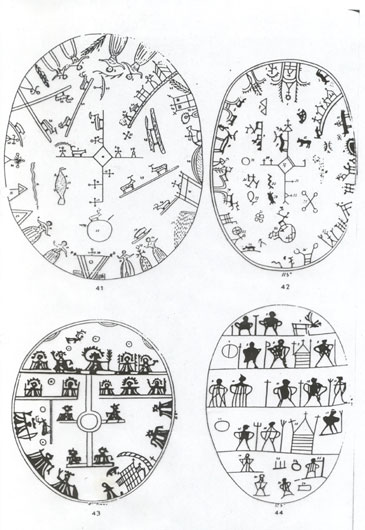

Kuvia noitarumpujen kalvopinnoilta: Ylimpänä on Radien-kolminaisuuden kuva mahdollisesti taivaan eri tasoja kuvaavan rakennelman päällä. Keskiaikainen kristillinen vaikutus näkyy myös hahmojen saamissa sädekehissä. Keskimmäiset hahmot esittävät Bieggagállis-tuulenjumalaa; lapioillaan hän sai ilman liikkeelle. Alimpana noaidi-hahmoja rumpuineen.

Raediella oli liuta osin kristillisen kolminaisuusopin mallin mukaan muodostuneita sivupersoonia. Kildininsaamelaisessa perinteessä tiedetään Jimmel-aaja (jimmel 'jumala', aaja 'äijä'), joka osallistui alkuajan eläinmaailman ominaisuuksien luomiseen. Jimmel-jumalalla ei perinteen mukaan kuitenkaan ole osuutta eläinten varsinaiseen syntyperään. Jumala ei määrää, vaan toteuttaa eläinten toiveita. Toteuttamisen mahdollisuuksien kannalta jimmel on aktiivinen luoja, luovien voimien keskittymä. Toiveiden toteuttaminen perustuu eläinmaailman omaan tietoisuuteen, joka on luonnon sisäistä, ei sen ulkopuolelta säädettyä tietoa. Myös pohjois- ja eteläsaamelaisilla on samaan aihepiiriin liittyviä kertomuksia. Käsitykset tästä jumalasta ja sen paikasta saamelaisessa mytologiassa olivat varsin hämäriä luultavasti jo ennen kristinuskon tuloa, ja ilmeisesti ne tulivat vielä monimutkaisemmiksi saamelaisten tutustuttua ortodoksiseen uskontoon. Kristilliset ja esikristilliset piirteet lienevät sulautuneet yhteen ja luoneet jumala-äijän synkretistisen hahmon.

Rombikuvio on tulkittu auringon merkiksi siitä lähtee neljä symbolista sädettä. Máttaráhkká-vaimo tyttärineen näyttää edellisessä olevan rumpukalvon alalaidassa (neljä naishahmoa). Niitä muistuttavat hahmot ylhäällä kuuluvat todennäköisesti taivaanylisen jumalan piiriin. Ruton ratsastajahahmo näkyy edellisessä n. ”kello kolmessa” ja jälkimmäisessä ”kello kahdessa”. Kummassakin tapauksessa sen paikka on täyden tai miltei täyden kierroksen päässä – siis mahdollisimman kaukana – taivaanylisistä jumalista, jos rumpukalvon kehää kiertäviä kuvioita luetaan vastapäivään ylhäältä alkaen.

Taivaallisiin jumaliin on tapana laskea ainakin Beaivi (Aurinko), Mánnu (Kuu), ukkosen- ja tuulenjumalat sekä Madder-Attje. Useimpien jumaluuksien palvonta oli sukupuolisidonnaista. Ainoastaan taivaanjumala Raedienin ja Auringon palvonta oli yhteistä kummallekin sukupuolelle. Tiedot naisten kultillisesta toiminnasta ovat varsin puutteellisia, koska lähteitten kokoajat eivät siitä ole yleensä olleet kiinnostuneita. Aurinko liitetään saamelaisessa perinteessä kautta Saamenmaan hedelmällisyyteen sekä saamelaisten ja porojen alkuperään. Kuu esiintyy saamelaismytologiassa joillain perinnealueilla porojen vasomisen suojelijana. Saamelaiset ovat liittäneet siihen myös tuhoavia, vaarallisia myyttihahmoja, kuten Áhčešeátne (Áhčešeátne - Njávešeátne) tai hänen poikansa Askovis. Itäisemmillä saamelaisilla taivaanjumala näyttää sulautuneen ukkosen jumalaan. On ehdotettu, että itäsaamelaisten tuntema ukkosenjumala Tiermes, jota vastaa pohjoissaamen Dierpmis ja joka lienee suomalais-ugrilaista perua, olisi alkuperäinen saamelainen taivaanjumala. Näin Raedie olisi skandinaavisista ja saamelaiseen kulttuurin jo ennen kristinuskon varsinaista tuloa tihkuneista kristillisistä aineksista muotoutunut myöhempi tulokas. Tuulimies, Bieggagállis tai Bieggaolmmái tunnetaan kautta Saamenmaan; sillä oli vaikutusta saamelaisten pääelinkeinoihin, pyyntiin ja myöhemmin poronhoitoon.

Tässä eteläsaamelaisessa aurinkokeskisessä rummussa ”tuulimies” näyttää seisovan yhdellä auringon symbolisista säteistä. Kun taivaanylinen jumala Radien on rummun yläosassa, osoittaa asetelma tuulenjumalan sijoittuvan samalle ”tasolle” Auringon kanssa, ja tulkinnan mukaan taivaanylistä jumalaa ”alemmaksi”.

Maanpäällisistä jumalista tiedetään metsästyksen jumala Leaibeolmmái, leppämies, kasvillisuuden jumalatar Rananeid, ihmisten kantaisä Madder-Attje Máttaráhkká-vaimoineen ja tämän tyttärineen.

Rananeid eli Ruonaneid (ruoná 'vihreä'; nieida 'neito') on eräitten norjalaisten lähteitten tuntema feminiininen jumaluus, joka Leemin mukaan laskettiin lähimmäksi taivaanylistä jumalaa. Rananeidin sanottiin asuvan korkeimmalla tähtitaivaalla vain vähän alempana kuin Raedienin. Rananeid oliniiden tunturien jumaluus, jotka ensinnä viheriöivät keväisin, ja hän antoi uuden ruohon kasvaa porojen ravinnoksi. Hänelle saamelaisten tiedetään uhranneen, jotta porot tulisivat ajoissa ruoholaitumelle. Tätä jumaluutta vastaa turjan- ja kildininsaamelaisessa perinteessä tunnettu kasvillisuuden haltijatar Raa z-ajk (raa ss 'ruoho, kasvillisuus', ajk 'emo').

Madder-Attje, tai eteläsaamessa Maadteraajja, ihmisten kantaisä (maadter ~ esi-, kanta-), on luultavasti vain suppealla eteläsaamelaisalueella tunnettu jumaluus, jolla oli selvä yhteys saamelaiseen noitaan. Eräiden 1700-luvun lähteiden mukaan ainoastaan mahtavimmat noidat saattoivat piirtää Maadteraajjan kuvion omille rummuilleen, ja vain heillä oli mahdollisuus ottaa yhteys kantaisään. Toiseksi ainoastaan mahtavilla noidilla oli tieto siitä, kuinka ihmissuku sai alkunsa. Enemmän tietoja on Maadteraajjan vaimosta ja hänen tyttäristään, jotka tunnetaan etelä- ja pohjoissaamelaisalueella. Näillä feminiineillä jumaluuksilla on yhteys elämän alkuun ja loppuun ja erityisesti naisiin ja naisten toimintaan.

Eteläsaamelaisessa perinteessä tunnetaan useita aahka-naisjumalia. Maadteraahkalla (aahka ~ vanha nainen, akka), kantaäidillä on kolme tytärtä, joita enimmäkseen naiset palvelivat: Saaraahka, (mahd. luova akka), Joeksaahka (jousiakka) ja Oksaahka (oviakka), jotka asuivat kodan alla naisten sakraalilla vyöhykkeellä miesten sakraalia vyöhykettä boaššua vastapäätä. Nämä jumalattaret liittyivät erityisesti suvunjatkamiseen. Eteläsaamelaisaluetta (Trøndelag) koskevat 1700-luvun lähteet kuvaavat näiden jumaluuksien toimintaa seuraavasti: Kun Raedie oli luonut ihmissielun, hän lähetti sen Maadteraajjalle, joka Raedien määräyksen mukaan toimitti sen edelleen puolisolleen Maadteraahkalle. Tämä puolestaan luovutti sen edelleen tyttärilleen, joista Saaraahka oli varsinainen raskauden ja synnytyksen jumalatar. Joeksaahka auttoi ja suojeli naista synnytyksessä ja se kykeni muuttamaan kohdussa olevan tyttölapsen poikalapseksi, jos sille uhrattiin hyvin. Joeksaahkan yhteys metsästykseen ilmenee jo jumalattaren nimestä; hänellä oli yhteys metsästyksen jumalaan (Leaibolmmái), jonka suojelukseen Joeksaahka antoi poikalapsen synnytyksen jälkeen. Oksaahkan velvollisuuksiin kuului seurata pientä lasta syntymän jälkeen siihen saakka, kun lapsi alkaa kävellä. Suomen puolen pohjoissaamelaisilta tunnetaan vain Máttaráhkká, ei hänen tyttäriään. Ruotsin puolella tunnettiin 1800-luvun tietojen mukaan Sáráhkká. Hänen asuinpaikkansa oli tulisijan vieressä. Saamelaisesta myöhäisperinteestä tiedetään kristillisten toimitusten mallin mukaisesti muodostunut synkretistinen Sáráhkká-kultti, joka ei kuulunut yksinomaan naisille, vaan joka oli myös miesten suosima.

Maanalisiin jumaluuksiin voidaan lukea Jábmiidáhkká, vainajalan (kuolema ja vainajat) hallitsija ja Ruto, kulkutautien jumaluus ja ehkä yleisemminkin maailman pimeän puolen hallitsija. Jábmiidáhkká on keskeinen naispuolinen maanalinen jumaluus, joka toisaalta salli vainajasielujen aiheuttaa eläville vakavia sairauksia, toisaalta taas oli maanpäällistä muistuttavan ja sikäli kutakuinkin onnellisen olotilan valtiatar. Ruto oli mahtava vastustaja ihmisille, jopa noidille ja myös jumalille. Ruton symboliksi tulkitaan noitarummuilla saamelaiskulttuureille vieras hevonen, joita saamelaisten tiedetään uhranneen Rutolle. Hevosuhrin ja -symboliikan perusteella Rutoa on pidetty lainattuna elementtinä saamelaisessa maailmankuvassa. Vanhempi kirjallisuus yhdistää Ruton skandinaavien Odiniin. Rutolle voidaan kuitenkin löytää suoranaisia vastineita Siperian suomensukuisten kansojen joukosta.

Rombikuvio on tulkittu auringon merkiksi siitä lähtee neljä symbolista sädettä. Máttaráhkká-vaimo tyttärineen näyttää edellisessä olevan rumpukalvon alalaidassa (neljä naishahmoa). Niitä muistuttavat hahmot ylhäällä kuuluvat todennäköisesti taivaanylisen jumalan piiriin. Ruton ratsastajahahmo näkyy edellisessä n. ”kello kolmessa” ja jälkimmäisessä ”kello kahdessa”. Kummassakin tapauksessa sen paikka on täyden tai miltei täyden kierroksen päässä – siis mahdollisimman kaukana – taivaanylisistä jumalista, jos rumpukalvon kehää kiertäviä kuvioita luetaan vastapäivään ylhäältä alkaen.

Rajan vetäminen jumalien ja muiden tuonpuoleisten olentojen välille on vaikeaa ja osin mielivaltaista, vain muodostuneeseen käytäntöön pohjaavaa. Tämän- ja tuonpuoleisuus ylipäätään muodosti saamelaisille pikemminkin jatkumon kuin länsimaistyyppisen arkisen ja pyhän dikotomian. Lähelle jatkumon toista, tämänpuoleisen, päätä sijoittuivat monenlaiset näkyvät ja näkymättömät kanssaeläjät (haltijat, maahiset), joiden huomioonottaminen usein vaati vain arkista kohteliaisuutta. Jatkumon keskivaiheille sijoittuivat seitakivet (sieidi) mahtavine, mutta osin vielä inhimillisiä piirteitä omanneine henkineen. Jumaliksi on tässä yhteydessä luettu jatkumon toiseen päähän sijoittuneet näkymättömät mahdit, joiden puoleen voitiin kääntyä vain rukouksin ja uhrein.

Sisällysluettelo: Muinaisusko, mytologia ja folklore

Pre-Christian gods

According to the vertical picture of the world depicted in the segments of shamans drum skins, the pre-Christian gods of the Saami can be divided into those that lived above the sky, those that dwelt in the sky, the gods of the earth, and the gods of the underworld. Information about these old gods is uncertain, open to interpretation and relatively late. It was gathered only during the most intensive period of missionary activity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and mainly in Sweden and Norway. By this time, the old Saami conceptions of the gods had already become blurred. On the one hand, Scandinavian and also Christian influences infiltrated the pre-Christian world view especially of the western Saamis. On the other hand, the fact that the material was gathered in languages other than Saami was a potential source of errors: the interpreter or the Saami informant himself might adapt the names of the Saami gods to ancient Scandinavian mythology in order to make his own ideas more comprehensible to outsiders. Moreover, those who gathered the classic sources, generally missionaries, already imposed their own interpretations on what they were told, and what their informants wanted to tell them. And the oldest sources, which date back to a time when the ancient religion of the Saami was still alive, were generally produced on the basis of material gathered and interpreted by missionaries among the western Saami. Nor is it clear to what extent the existing information truly represents the knowledge of the shamans, the religious specialists of the Saami, and to what extent it is a reflection of the collective tradition, the views of the whole people.

A god above the sky. The Sky God, who was the upholder of order in the world, can be considered to have lived above the sky. The information about him comes from the western Saami regions. In the regions where South and Ume Saami were spoken, his name (the names are here given in the forms in which they appear in the old sources) was Radien (also Mailmen Radien Radien of the World ), and further to the north and east in Pite, Lule and the North Saami of the Torne area Veralden Olmai the Man of the World (< Swedish värld world ) or Veralden-Radien Radien of the World (Raedie, the Sky God). The names point to a strong Scandinavian influence. The proportion of Christian borrowings is apparent from the fact that Raedie is depicted on the shamans drums in the form of a trinity; Raedie had a whole group of avatars, some of which were formed according to the Christian doctrine of the trinity. In the Kildin Saami tradition, the god Jimmel-aaja (Jimmel god, aaja old man ) took part in the creation of the animal world, although according to tradition he had no part in the actual creation of the animals themselves; Jimmel fulfilled the wishes of the animals rather than determined them. He was an active creator, a concentration of creative forces. The fulfilment of the wishes of the animals is based on an awareness of the animal world, which is within nature itself, not externally imposed knowledge. The North and South Saamis have similar myths. Ideas about this god and his place in Saami cosmology were probably very vague even before the advent of Christianity, and they obviously became even more complicated when the Saami came into contact with the Orthodox religion. Christian and pre-Christian features probably coalesced to create a syncretic figure of a god who was an old man.

The sky gods are usually thought to include at least Beaivi (the Sun), Mánnu (the Moon), Bajánalmmái, the God of Thunder, Bieggaolmmái, the God of the Winds, Rananeid, the goddess of vegetation and Madder-Attje, the forefather of man. The worship of most deities was according to sex; only the worship of Raedie and the Sun was common to both sexes. Information about female cult practices is extremely deficient because those who collected the source material were not generally interested in them. In the Saami tradition, the Sun is associated throughout Saamiland with fertility and the origins of the Saami and of the reindeer. The Moon in some areas of the Saami tradition appears in mythology as the protector of reindeer at calving time; however, the Saami also linked the Moon with destructive mythical figures like Áhčešeatne and her son Askovis. For the eastern Saami, the Sky God seems to have merged with the God of Thunder. It has been suggested that Tiermes, the God of Thunder of the eastern Saami, who corresponds to the North Saami Dierpmis and was probably of Finno-Ugric origin, was the original Saami Sky God. This would mean that Raedie was a later arrival formed out of Scandinavian and Christian elements that filtered into Saami culture before the advent of Christianity proper. The God of the Winds, Bieggagállis or Bieggaolmmái, was known through Saamiland; he affected the major sources of livelihood of the Saami: hunting, and later reindeer herding.

Rananeid or Ruonaneid (ruoná green, nieida maiden ) was a female divinity found in certain Norwegian sources, who according to Leem was considered to be closest to the God above the sky. Rananeid was said to dwell high in the firmament just a little lower than Raedie. She was the goddess of those mountains and fells that first turned green in the spring, and she allowed the new grass to grow as food for the reindeer. It is known that the Saami sacrificed to her so that the reindeer wouldreach the grass pasturages in time. This divinity corresponds to the spirit of plants Raa z-ajk (raa ss grass, verdure, ajk mother) of the Ter and Kildin Saami tradition.

Madder-Attje (in South Saami Maadteraajja), the Father of Man (madter pre-, proto- ) was a divinity that was known probably only in a limited South Saami area, and he was clearly associated with the Saami shaman (Shamanism). According to some eighteenth-century sources, only the most mighty shamans had the right to draw the symbol of Maadteraajja on their drums, and only they were able to contact the Father of Man. Moreover, the powerful shamans alone had a knowledge of the origins of mankind. Of the gods who dwelt on earth, it is known that there was a God of Hunting, Leaibeolmmái the Alder Man, a Goddess of Plants, Rananeid, and Máttaráhkká, the wife of Madder-Attje, and their daughters. Maadteraajja and the daughters were known in both the South and North Saami regions. These female divinities were connected with the beginning and end of life, and they were particularly associated with women and their activities.

The South Saami tradition has numerous aahka female divinities. Maadteraahka (ahka old woman, hag ), the Mother of Man had three daughters; Saaraahka, (possibly Creative Old Woman), Joeksaahka (Old Woman of the Bow) ja Oksaahka ( Old Woman of the Door ). These were mainly worshiped by women, and they lived beneath the Lapp lodge under the area sacred to the women, which was situated opposite the boaššu, the sacred area of the men. They were mainly associated with procreation. Sources relating to the South Saami region (Trøndelag) describe the activities of these divinities as follows: When Raedie had created the human soul, he sent it to Maadteraajja, who in turn handed it over to his daughters, of whom Saarahka was the actual goddess of pregnancy and birth (Human being). Joeksaahka helped and protected women in birth-giving, and she was capable of changing a girl child in the womb into a boy if she was properly propitiated with sacrifices. The connection of Joeksaahka with hunting is already apparent from her name, and she was connected with the God of Hunting Leaibolmmái, to whose protection she entrusted a baby boy after birth. The duties of Oksaahka included watching over babies from the time they were born to when they began to walk. In the North Saami areas of Finland, only Máttaráhkká was known, not her daughters, although according to nineteenth-century sources a divinity called Sáráhkká was known in Sweden; she was believed to dwell beside the fireplace. In the late Saami tradition there existed a syncretic Sáráhkká cult that conformed to the model of Christian practices, and which was not associated with women alone but was also favoured by men.

The gods of the underworld included Jábmiidáhkká, the Ruler of the Underworld (Death and the dead) and Ruto, the God of Pestilence. Jábmiidáhkká was the major female underworld divinity, and while she allowed the souls of the departed to spread grave diseases among the living, she was also the ruler of a place that resembled the world above, and which was thus more or less a happy one. Ruto was a powerful enemy of man, even of shamans, and indeed of other divinities. The symbol of Ruto on the shaman's drum is interpreted as being the horse, which was foreign to Saami culture, and which the Saami are known to have made sacrifices to. Because of the horse sacrifices and the horse symbolism, Ruto has been considered an imported element in the Saami pantheon. Older scholarly literature linked Ruto with the Scandinavian god Odin. However, it is possible to find direct counterparts of Ruto among the Finnic peoples of Siberia.

It is difficult, and to some extent arbitrary, to draw a line between gods and other supernatural creatures, and it is based merely on convention. For the Saami, this world and the supernatural generally constituted a continuum rather than a Western type of dichotomy between the secular and the sacred. Close to the worldly end of the continuum there existed all kinds of visible and invisible fellow creatures, whose acknowledgement often required no more than ordinary observance; in the middle of the continuum were the shines with their powerful spirits who nevertheless still assumed partly human features. In the present context, gods are considered to be those invisible powers located at the other end of the continuum, beings who could only be approached with prayers and sacrifices.

Table of contents: Saami Pre-Christian world view, mythology and folklore