Nature in the North

Pohjoinen luonto

Luonto on kasvien, eläinten ja pieneliöiden sekä maiseman (tunturit, joet jne.) muodostama kokonaisuus, jossa myös ihminen elää. Pohjoisten alueiden luonto on omaleimainen.

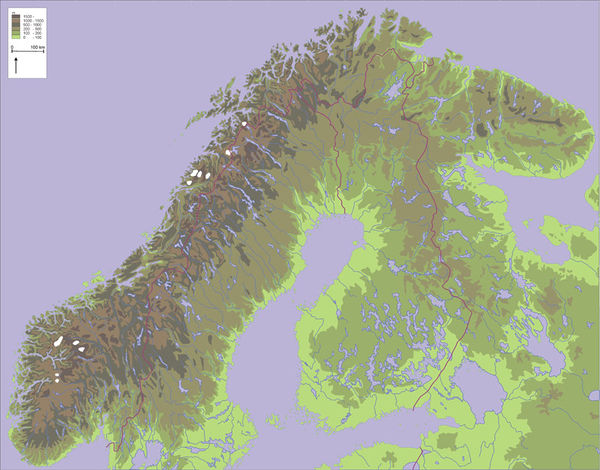

Hallinnollisesti Lappi on Lapin lääni, Perämeren pohjukasta Kilpisjärvelle ja Utsjoelle ulottuva lähes 100 000 neliökilometrin laajuinen alue. Alueella elää sekä ihmisiä että poroja n. 200 000 eli molempia n. kaksi eläintä neliökilometrillä. Luonnonmaantieteellisesti Lappi on kuitenkin enemmän kuin Lapin lääni, sillä Suomen rajojen ulkopuolella samantapaista Lappia on Ruotsissa (Norrbottenin lääni), Norjassa (Tromssan ja Finnmarkin läänit) ja Venäjällä (Kuolan niemimaa). Tästä neljän valtakunnan maasta käytetään yleisesti nimeä Pohjoiskalotti. Kölivuoristoa pitkin luonnonmaantieteellinen Lappi ja saamenkulttuurin alue ulottuvat kuitenkin Jyväskylän korkeudelle (62 °N) asti.

Kansallis- ja luonnonpuistot muodostavat Suomen luonnonsuojelualueverkon perustan. Lapin suurimmat kansallispuistot ovat Lemmenjoen ja Urho Kekkosen puistot. Suojeltujen alueiden suuri määrä on aiheuttanut Lapissa maankäyttökiistoja. Viime vuosikymmeninä suojelualueiden arvo on alettu nähdä uudella tavalla, koska niistä on tullut Lapin merkittävin matkailuvaltti. Kansallispuistojen ohella Lapissa on erämaa-alueita selvästi enemmän kuin muualla maassa. Erämaa-alueet eivät ole varsinaisia luonnonsuojelualueita, vaan niiden tavoitteena on erämaisuuden (tiettömyyden) säilyttäminen. Erämaa-alueet ovat tärkeitä porolaitumia.

Suomen saamelaisten nykyisin asuttama alue voidaan jakaa karkeasti kahteen osaan, Metsä-Lappiin ja Tunturi-Lappiin, joiden luontaisena rajana on havupuiden, outamaiden, pohjoisraja (kasvisto). Mäntymetsäraja kulkee Suomessa maaston muotoja mutkitellen lännestä itään Karesuvannosta Näätämöjoen pohjoispuolelle. Metsä-Lappi on osa Pohjoiskalottia kiertävää taigaa eli havumetsävyöhykettä.

Tunturikoivikko on taigan ja puuttoman tundran välinen vaihettumisvyöhyke. Tunturi-Lappia ovat 5-10 metrin korkuista kituliasta metsää kasvavat tunturikoivikot ja puuttomat tunturipaljakat. Lähes kaikkialla muualla maailmassa havupuut ovat metsänrajapuuna. Tunturikoivun metsänraja on Länsi-Lapissa n. 600 m ja Itä-Lapissa n. 400 m merenpinnan yläpuolella. Oikeastaan vasta n. 900-1 000 m korkeudessa, siis meillä ainoastaan Käsivarren suurtuntureilla, metsien aluskasvit kuten mustikka eivät enää menesty. Siellä täällä Metsä-Lapin metsäerämaan eli kairan keskeltä kohoavien poikkeuksellisen korkeiden erillisten tuntureiden - Ylläs, Levi, Pallas-Ounas, Sokosti, Kiilopää, Värriö - lakiosat ovat myös Tunturi-Lapin luonteisia.

Lapin luontoa luonnehtii suuri vuodenaikojen välinen vaihtelu. Pitkä, kylmä ja luminen talvi alkaa lokakuussa ja loppuu maaliskuun lopulla, lyhyt ja kohiseva kevät muuttuu toukokuun lopulla lyhyeksi, valoisaksi, mutta kylmäksi kesäksi, jossa jo elokuun alkupuolella on nähtävissä syksyn merkkejä. Vuoden keskilämpötila määrää kasvukauden pituuden eri alueilla ja siten luonnon monimuotoisuuden ja vyöhykkeisyyden. Pohjoista kohti olosuhteet tavallisesti kovenevat. Esim. Metsä-Lapissa vuoden keskilämpötila on +1- -1°C, Tunturi-Lapissa -1- -2,5°C. Kilpisjärvellä vuoden lämpimimmänkin kuukauden,heinäkuun, keskilämpötila on alle + 11 °C. Golfvirran ansiosta Lapissa on kuitenkin varsinkin talvella huomattavasti lämpimämpää kuin samoilla leveysasteilla mannerten sisäosissa Venäjällä ja Kanadassa. Nyrkkisääntönä on, että pohjoinen eliöstö on lajiköyhää ja pinta-alayksikköä kohti lasketulta massaltaan vähäistä (eläimistö). Maamme etelärannikolla kasvaa esim. noin 950 putkilokasvilajia, mutta niin Enontekiön kuin Inarin Lapissa vain noin 450.

Varsinaista Tunturi-Lappia, jossa havupuu on hävinnyt kokonaan maisemasta, riittää Suomen puolelle vähemmän kuin naapurimaihin. Länsi-Lapissa se alkaa Kuttasen ja Leppäjärven kylien pohjoispuolelta, Itä-Lapissa Kaamasen kylästä. Kilpisjärven - Haltin seutuja lukuun ottamatta, jossa sijaitsee kymmeniä yli tuhannen metrin korkeuteen kohoavia tuntureita (korkein Halti 1328 m), Tunturi-Lappimme korkokuva on loivasti kumpuilevaa. Käsivarren suurtuntureiden itä- ja pohjoisrinteillä säilyy kesän lopulle asti laajoja lumilaikkuja , jasoja, mutta ikuisen lumen ja jään peittämiä maita meillä ei ole. Vaikka paljakka-alueemme onkin suhteellisen pienialainen, tuntureiden eliöyhteisöt muodostavat tärkeän osan Suomen luonnon monimuotoisuutta. Varsinkin monet kauniit kukkakasvit kasvavat vain tuntureilla ja ovat matkailullinen vetonaula. Tunturilinnut ovat samanlainen houkutin.

Avotunturia eli paljakkaa on monenlaista. Rehevillä niityillä kukkii heinä-elokuussa suhteellisen matalakasvuinen, mutta monipuolinen kasvilajisto, karummat tunturikankaat ovat jäkälien ja varpujen peitossa ja kaikkien karuimmilla mailla on pelkästään kivikkoa eli rakkaa.

Niityt sijaitsevat tavallisesti tunturien alarinteillä ja ne vapautuvat ensimmäisenä lumesta ja tarjoavat poroille tuoreen kevätvihannan talven jälkeen. Koivun ohella poro syö mielellään koivun kanssa symbioosissa eläviä tatteja. Saamelaiset ovat perinteisesti eläneet tunturikoivikon ja avotunturin muodostamassa rajamaassa ja liikkuneet vuodenaikojen mukaan rajan molemmin puolin. Ekologisesti heitä voidaan kutsua metsänrajankansaksi.

Havumetsien ja puuttomien tuntureiden lisäksi Lapin luontoon kuuluvat suot ja virtaavat vedet, niin suuret joet kuin pienet purot, joita usein peittävät tai reunustavat tiheät vaivaiskoivikot ja pajuviidakot. Vuolaita jokia on runsaasti: Torniojoki, Tenojoki, Ounasjoki, Kemijoki jne. Jos ihmisen rakentamia tekojärviä ei oteta lukuun, Lapissa on vähän suuria järviä. Tunnetuimmat ovat Inarijärvi idässä ja Kilpisjärvi lännessä. Metsä-Lapin suot ovat yleensä laajoja avosoita, aapoja. Tunturi-Lapissa on aapojen lisäksi palsasoita, joilla pesii poikkeuksellisen edustava lintulajisto, erityisesti kahlaajia, ja jotka ovat hyviä hillamaita (Lapissa hilla, muualla suomuurain tai lakka).

Palsoilla vuorottelevat vetiset painanteet ja jopa seitsemän metriä korkeat jättiläismäiset turvekummut, jotka ovat sisältä ikijäässä puolen metrin paksuisen sulan pintakerroksen alapuolella. Lapin vanhimmat palsat ovat noin 3 000 vuotta vanhoja. Palsojen ytimiä lukuun ottamatta Pohjoiskalotilla ei ole ikiroutaa niin kuin Siperiassa ja Pohjois-Amerikassa. Myöskään varsinaista tundraa ja arktista vyöhykettä ei Fennoskandiasta löydy. Meidän "tundra" on puutonta tunturia, jossa puuttomuus johtuu tunturin korkeudesta eikä riittävän pohjoisesta sijainnista. Meikäläisiä tunturikoivumetsiä ja sen yläpuolisia alueita kutsutaan useinsubarktiseksi eli puoliarktiseksi vyöhykkeeksi. Suomessa vältellään tundra-sanan käyttöä, vaikka saamenkielen "tuoddar" ja suomenkielen "tunturi" lienevät tundra-sanan kantana. Tundra voidaan määritellä kasvillisuuden perusteella: esim. tunturikohokkia, haproa ja sinirikkoa kasvavat maat ovat tundraa.

Saamenmaahan kuuluu myös Tunturi-Lapin pohjoispuolinen alue, Vuono- ja Meri-Lappi, jossa jylhät tunturit ja terävät vuoret laskeutuvat jyrkästi Jäämereen. Norjan tunturien korkeus johtuu siitä, että ne eivät ole nuoruutensa (n. 300 milj. vuotta) vuoksi ehtineet kulua kuten Suomen tunturit (n. 2 000 milj. vuotta). Vain Kilpisjärven seudulta löytyy "nuoria" Kölivuoriston itäreunan tuntureita. Tällä alueella tuntureiden väliset laaksot ovat melko jyrkkärinteisiä vankkoja (saameksi vagge). Pohjoisesta sijainnistaan huolimatta merenrannikko on ilmastoltaan mannerta selvästi lauhempi ja elollisen luonnon toimeentulolle suotuisampi alue. Golfvirran ansiosta Jäämeri pysyy sulana ympäri vuoden ja kasvukausi on pitkä, koska lumi sulaa rannikolta jopa pari kuukautta aikaisemmin kuin 50 km päässä sisämaassa. Kasvukausi, eli se aika vuodesta, jolloin vuorokauden keskilämpötila on vähintään +5 astetta, on Metsä-Lapissa noin 120-140 vuorokautta (etelärannikolla noin 180 vrk) ja Tunturi-Lapissa noin 100-120 vuorokautta. Tunturi-Lapissa maanviljely on tunnetusti vaikeaa pelkästään lyhyen kasvukauden vuoksi.

Yksilöt, elämän yksiköt, ovat luontoon sopeutuneita, jos ne elävät riittävän kauan kasvattaakseen lisääntymiskykyisiä jälkeläisiä ja estävät siten elämänlangan katkeamisen. Identtisiä kaksosia lukuun ottamatta korkeampien eläinlajien yksilöt syntyvät maailmaan erilaisina ja erilaisin eväin varustettuina. Saalistus, johon metsästyskin laajasti ottaen kuuluu, on osa pohjoisen luonnon kokemaa stressiä. Stressinsietokyky, joka vaihtelee yksilöstä ja lajista toiseen, on eliöiden tärkeitä sopeutumiskeinoja ympäristöönsä. Pohjoisilla alueilla saalistuspaineen ja muiden biologisten stressitekijöiden (esim. eliöiden kilpailu elintilasta) eivät ole yhtä tärkeitä kuin eteläisillä alueilla, koska sekä petoja että toistensa kanssa kilpailevia yksilöitä on vähemmän pinta-alaa kohti. Biologista stressinsietokykyä tärkeämpää on kyky sietää elottoman ympäristön, lähinnä sään, aiheuttamaa stressiä.

Pohjoisilla alueilla niin kasvit kuin eläimetkin elävät usein kylmänsietokykynsä äärirajoilla. Pohjoiseen sopeutumisen ehto on erityisesti eliöiden nuoruusasteiden kylmänsietokyky. Esim. aikuiset männyt ja kanalinnut kestävät hyvin ankaria oloja, mutta niiden kannat ovat tuhoon tuomittuja, jos olosuhteet ovat kesälläkin niin ankarat, että niiden lisääntyminen vaikeutuu. Mitä pohjoisemmaksi mennään, sitä todennäköisempiä ovat kesäaikaiset takatalvet ja pakkasjaksot ja niistä aiheutuva lisääntymisen lähes täydellinen epäonnistuminen. Porojen vasomisen onnistumisen kannalta touko-kesäkuussa saatavilla olevan uuden kasvisravinnon määrä on tärkeä: jos kesän tulo, esim. tunturikoivujen puhkeaminen lehteen, viivästyy, vasominen on vaarassa. Kasveilla pohjoiseen sopeutumisen ehtoja ovat hyvän pakkaskestävyyden ja lyhyen kasvukauden aiheuttamien ongelmien voittamisen ohella sopeutuminen Lapin yöttömään yöhön, maaperän alhaiseen ravinnepitoisuuteen ja kasvissyöjien aiheuttamaan ravinne- ym. menetyksiin. Eläimille, esim. pesimälinnuille, kesäyön valoisuudesta on sikäli hyötyä, että ne voivat pidentää aktiivisuusaikaansa ja ruokailla läpi vuorokauden. Lapin ihmisten vuorokausirytmi muuttuu samalla tavalla vuodenaikojen mukaan.

Metsänraja on merkki erityisen voimakkaasta stressialueesta, jolla tietty luonnonelementti (esim. kuusi, mänty, koivu) on tullut sopeutumisensa äärirajalle eikä enää menesty tuon rajan pohjois- tai yläpuolella. Esim. mänty tarvitsee 2-3 perättäistä lämmintä kesää, jotta siemenmuodostus ja taimen kehitys onnistuisivat. Koska metsän uudistuminen on äärioloissa epävarmaa, sen hakkaamisen ja muun taloudellisen käytön on oltava hellävaraista. Esim. Länsi-Lapissa talousmetsien ja ns. suojametsien välinen raja sijaitseekin noin 300 m varsinaisen metsänrajan alapuolella. Jos ankaria "minimivuosia" sattuu useita peräkkäin, kasveilta loppuu energia, eivätkä ne jaksapuolustautua tuhohyönteisiä, kuten tunturimittaria, vastaan ja kärsivät suuria tuhoja. Pahimmillaan tunturimittarin toukat ovat hävittäneet tuhansia neliökilometrejä koivikkoa. Voimakas tyvivesojen muodostus on ainoita keinoja, joilla tunturikoivu voi toipua mittarituhosta.

Puiden elämän mahdollisuuksien loputtua myös niistä suojaa tai muuta hyötyä saavat eläimet saavuttavat elämisen mahdollisuuksiensa rajan ja joko kuolevat tai muuttavat pois alueelta. Saamelaiset ja porot ovat käyttäneet hyväkseen metsärajamaita ja liikkuvat sen pohjois- ja yläpuolelle suotuisana kesäkautena ja pakenevat sieltä talven stressiä outamaille. Ilmaston muutokset, mm. ns. kasvihuoneilmiöstä johtuva ilmaston lämpeneminen, näkyvät nopeasti pohjoisilla "stressivyöhykkeillä" lämpimiin oloihin sopeutuneiden eteläisten lajien (esim. ketun) runsastumisena ja kylmään sopeutuneiden, mutta toisten lajien kilpailua huonosti kestävien lajien (esim. naalin) taantumisena. Ennen fossiilisten polttoaineiden kautta metsänraja oli usein myös pysyvän ihmisasutuksen raja, jonka takana ei voinut elää ympärivuotisesti (eskimot eli inuiitit perustivat kulttuurinsa merinisäkkäiden rasvaenergiaan).

Eliöt voivat sopeutua äärimmäisen kylmiin olosuhteisiin monella tavalla. Poromiesten ja porojen tavoin useimmat linnut muuttavat talveksi suotuisammille alueille. Liikkumalla järkevästi vuodenaikojen tarjoamien resurssien mukaan vähätuottoisesta pohjoisesta luonnosta saadaan mahdollisimman paljon irti ja annetaan luonnolle myös aikaa uusiutua. Kesä- ja talvilaidunten välisen muuton eli jutaamisen loppuminen ja korvautuminen suppealla alueella pysymisellä ympäri vuoden on johtanut etenkin talvilaidunten heikkenemiseen ja talvisen "hätäruokinnan" välttämättömyyteen. Koska ruoka-apu tulee pääosin poronhoitoalueen ulkopuolelta, poronhoito ei ole enää entisenlaista ekologista, luonnon kantokyvyn varassa kehittyvää taloutta. Erityisesti pohjoisimmissa paliskunnissa jäkälästä onkin muodostunut porotalouden pullonkaula. Poronhoitokulttuurin muutokset heijastuvat väistämättä myös saamenkulttuuriin.

Lumi on Lapin tunnuspiirteitä. Luonnolle lumesta on sekä hyötyä että haittaa. Lumi katkoo mm. puita ja vaikeuttaa eläinten liikkumista ja ruokailua. Avotunturissa ympäri vuoden lumen päällä eläviä selkärankaislajeja on hyvin vähän: kiiruna, tunturihaukka, korppi ja naali. Kiirunaa lukuun ottamatta ne ovat lihansyöjiä. Pienemmät eläimet selviävät talvesta hengissä vain lämmittävän ja tuulelta suojaavan lumipeitteen alla. Jos lunta on metrikaupalla, lämpötila pysyy maanpinnassa kovimmillakin pakkasilla nollan tienoilla, minkä vuoksi pikkujyrsijät voivat lisääntyä myös talvella. Kanalinnut ja jopa pikkulinnut viettävät kaamosyön lumikiepissä. Tiaisten ruumiinlämpö saattaa laskea jopa kymmenen astetta yön aikana, mikä on erinomainen keino säästää energiaa. Samoin kuin rakennuksissa, ruumiin lämpötilan laskeminen vähentää lämmityskustannuksia. Toinen tapa säästää energiaa on lisätä eristettä. Esim. metsäjäniksen kesäturkissa on 200-300, talviturkissa jopa 700, karvaa neliösenttimetrillä. Pelkkä eristäminen ei luonnollisesti riitä, vaan tarvitaan myös polttoainetta. Monet eläimet turvaavat polttoaineen saannin keräämällä talveksi ruokavarastoja.

Heti metsänrajan tuntumassa on enemmän elämää talvellakin, eikä alueen lajikoostumus juuri poikkea ympäröivien metsien lajistosta. Siellä viihtyvät linnuista mm. riekko, hömötiainen ja lapintiainen, nisäkkäistä jänis, kärppä ja lumikko. Kylmyys ei usein ole suoranainen este eläinten selviämiselle arktisessa talvessa, vaan ravinnon puute. Hyvän tunturikoivun siemensadon turvin satapäiset urpiaisparvet, jotka yleensä muuttavat ainakin Etelä-Suomeen, talvehtivat joinakin vuosina metsänrajalla asti.

Sisällysluettelo: Luonto

Nature in the North

Nature is the entity composed of flora, fauna and micro-organisms together with the landscape (fells, rivers, etc.), and is also the habitat of man. The northern regions have a unique natural environment.

Administratively, Finnish Lapland consists of the Province of Lapland. It extends from the end of the Gulf of Bothnia to Kilpisjärvi and Utsjoki, an area of almost 100,000 square kilometres. The area is the home of about 200,000 persons and reindeer, that is about two creatures per square kilometre. In terms of natural geography, however, Lapland as a whole is more than the Finnish Province of Lapland because outside the borders of Finland it also extends into Sweden in the Province of Norrbotten, into Norway in the Provinces of Tromso and Finnmark and into the Russian Republic in the Kola Peninsula. Lapland and the area of Saami culture extend along the Kolen Mountains as far south as latitude 62º N.

The network of nature conservation areas consists mainly in national and nature parks. The largest national parks in Finnish Lapland are the Lemmenjoki National Park and the Urho Kekkonen National Park. The large number of protected areas has caused disputes over land use in Lapland. However, over the last few decades people have come to see the value of the protected areas in a new light as they have become the region's biggest tourist attraction. Apart from the national parks, there are also more wildernesses in Lapland than elsewhere in Finland. The wilds are not nature conservation areas as such, although the aim is to conserve their (roadless) nature as wildernesses. They are also important as pasturages for reindeer.

The area today inhabited by Finnish Saami people can be roughly divided into two parts: Forest Lapland and Fell Lapland, with a natural border created by the northern limit of the conifer belt and the forests (flora). The pine forest line meanders along the contours of the terrain in Finland from Karesuvanto in the west to north of the River Näätämöjoki in the east. Forest Lapland is part of the taiga, a swampy coniferous belt stretching across Lapland.

A belt of mountain birch stands forms an intervening zone between the taiga and the treeless tundra (Duottar/fell). Fell Lapland consists of this belt of mountain birches, which grow to a height of 5-10 metres and the bare slopes of the fells. Almost everywhere else in the world, it is conifers that constitute the tree line.

In western Lapland the mountain birch forest line is about 600 metres above sea level and in eastern Lapland about 400 metres. It is not until an altitude of about 900-1000 metres that forest undergrowth plants like bilberries no longer thrive. In Forest Lapland, too, there are some individual fells (e.g. Ylläs, Levi, Pallas-Ounas, Sokosti, Kiilopää and Värriö Fells) of the type found in Fell Lapland, with exceptionally high peaks rising out of the forests.

The nature of Lapland is characterized by great differences in seasonal change. The long, cold, snowy winter begins in October and ends in late March, the short, rushing spring changes at the end of May into a brief, light but cold summer, and by the end of August the signs of autumn are already visible. The average annual temperature determines the length of the growing season in different areas and thus the polymorphism of the flora and its division into zones. Generally conditions become harsher towards the north. For example, in Forest Lapland the average annual temperature is +1 -1ºC, while in Fell Lapland it is -1 -2.5ºC. In Kilpisjärvi the average temperature of the hottest month of the year, July, is below +11ºC. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, however, Lapland is-considerably warmer in winter than interior parts of continental Russia and Canada at the same latitude. Roughly speaking, the population of living organisms in the north is poor in terms of the number of species and sparse in size per unit of land area (fauna). For example, where as in southern Finland there grow about 950 varieties of vascular plants, in both Enontekiö and Inari in Lapland the equivalent number is about 450.

There is less of Fell Lapland proper, where conifer trees have disappeared altogether, in Finland than in her neighbouring countries. In western Finnish Lapland, it begins north of the villages of Kuttunen and Leppäjärvi, and in eastern Lapland it starts from the village of Kaamanen. Apart from the areas around Lake Kilpisjärvi and Haltti, in which there are dozens of fells rising over 1000 metres (the highest being Haltti Fell 1328 m), Fell Lapland generally has gently rolling contours.

The eastern and northern slopes of the big fells of the 'Arm of Finland' (the northwestern strip of territory projecting into Norway) still have patches of snow on them even at the end of summer, although there are no areas in Finland that are for ever covered with snow and ice.

Even though the bare upland region in Finland is relatively small in area, the communities of living organisms in the fells constitute an important part of the variety of nature in Finland. A particularly large number of beautiful plants grow on the fells, and they are an important tourist attraction as is also the bird life there.

The bare upland area is varied. There are lush meadows in July and August where there grows a wide range of relatively low-growing plants, while the more barren moors of the fells are covered with lichen and twigs, and in the most desolate parts of all there is nothing but rocks. The meadows are usually situated on the lower slopes of the fells, and they are the first to shed their covering of snow and offer the reindeer some fresh spring vegetation after the winter. Apart from the birch shoots and leaves, the reindeer eat the boletus fungi that grow in a symbiotic relationship with the birches. The Saami have traditionally lived on the border between the mountain birch belt and the open fells, moving each side of this line according to the season. Ecologically, they could be described as a tree line people.

In addition to the conifer forests and bare fells, Lapland is characterized by swamps and flowing waters, from big rivers to small streams, which are often covered or fringed by stands of mountain birches or willow thickets (ecology).

There are numerous fast-flowing rivers: Torniojoki, Tenojoki, Ounasjoki, Kemijoki, and so on. Apart from artificial reservoirs, there are few large lakes in Finnish Lapland. The best known are Inarijärviin the east and Kilpisjärvi in the west. The swamps of Lapland are generally broad, open marshy tracts (Áhpi). In addition to these there are also palsa bogs, in which an exceptionally large number of bird species nest, in particular waders. These peat bogs are also abundant in cloudberries. In the palsas, watery hollows alternate with huge turf mounds (often up to seven metres high), which, apart from an unfrozen half-metre deep superficial layer, are in the grip of the permafrost. The oldest palsas in Lapland are about 3000 years old.

I Apart from the cores of the palsas, there is no permafrost in the Arctic area of Fennoscandia as there is in Siberia and North America. Nor is there any tundra proper or Arctic belt. The 'tundra' in Finland is the treeless fell region, whose lack of trees is a result rather of its altitude than its northern location. The word 'tundra' is not used in Finnish to describe this region, although the Saami word duottar, and the Finnish tunturi, 'fell' are probably related to it. The tundra can be defined by its flora: for example land on which moss campion (Silene acaulis), mountain sorrel (Oxyria digyna) and purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia) grow is tundra.

The land of the Saami also includes the area north of Fell Lapland, the region of fjords and the sea, where the mighty fells and mountains fall sharply into the Arctic Ocean. The height of the Norwegian mountains is a result of the fact that, because of their young age (approx. 300 millionyears), they have not yet been eroded like the Finnish fells, which are 2,000 million years old. In Finland, only in the Kilpisjärvi region on the eastern side of the Kolen Mountains are there 'young' fells. The valleys between the fells in this area have fairly steep sides (vággi). Despite its northern location, the climate of the coast is distinctly milder than that of the interior, and it provides a more favourable environment for living organisms. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, the Arctic Ocean remains unfrozen throughout the year, and the period of growth is relatively long, because the snow melts on the coast two months earlier than it does 50 kilometres inland. The period of growth, i.e. the time of the year when the average daily temperature is at least +5ºC, in Forest Lapland is about 120 140 days (on the south coast about 180 days) and in Fell Lapland about 100-120 days. In Fell Lapland agriculture is notoriously difficult because of the short growing season.

Individuals,the basic units of life, can be considered to have adapted to nature if they live long enough to raise procreative offspring and thus prevent the chain of life from being broken. Apart from identical twins, the individuals of the higher animal species are all different and come into the world differently equipped. Predation, which includes hunting in the broad sense, is part of the stress incurred by nature in the north. The tolerance level of this stress, which varies from one individual and one species to another, is one the major factors of adaptation to the environment. In northern regions, the pressure from predation and other biological stress factors (for example, competition between organisms for territory) are less significant than in the south because both predators and competing individuals of the same species are fewer in number in relation to the land area. More important than biological stress tolerance is the ability to endure the stress caused by the abiotic environment, in particular the climate.

In northern climes, both flora and fauna often live at the limits of their ability to survive the cold. One condition of adaptation to the north is the ability of young organisms to endure the cold. For example,adult pines and fowls can survive extremely severe conditions, but their stocks are doomed to extinction if conditions in summer are so harsh that their procreation is imperilled. The further north one goes, the more likely are wintry spells and frosts in summer and the consequent almost total failure of reproduction. The calving of reindeer depends crucially on the availability on new vegetation for food in May and June. In addition to a good ability to withstand frost and to overcome the problems of a short growing season, the adaptation of plants to conditions in the north is conditional upon their ability to tolerate the 'nightless' days of the Lapland summer, the low nutrient content of the earth and the depredations of herbivores. On the other hand, the white nights of summer are useful to some animals, for example nesting birds, in that they lengthen the time when they can be active, and they are able to feed around the clock. The daily rhythm of people who live in Lapland similarly changes according to the season.

The tree line is a sign of an area of particularly strong stress, in which a particular natural element (e.g.the spruce, the pine or the birch) has reached the limit of its adaptability and no longer thrives above or north of that line. For example, the pine needs 2 3 warm summers in succession for seeding and germination to succeed. Because forest regeneration is uncertain in extreme conditions, felling and other forms of commercial exploitation must be carried out with discretion. For example, in western Lapland the border between commercial forests and so-called protected forests lies about 300 metres below the actual tree line. If there are several hard years in succession, the trees suffer a loss of energy and are unable to defend themselves against insect pests, such as the autumnal moth, and they suffer great devastation. At their worst, the larvae of the autumnal moth have destroyed thousands of square kilometres of mountain birch. One of the only ways the tree has of recovering from the depredations of the autumnal moth is to grow strong.

When the conditions for the survival of trees disappear, then the animals that are protected by them or otherwise exploit them also reach the limits of their ability to survive and either die out or migrate. The Saami and the reindeer have exploited the tree line belt, moving above or north of it in the favourable summer season and escaping the stress of winter in the forests. Climatic changes, including the increase in the temperature of the atmosphere resulting from the so-called greenhouse effect, are quickly evident in the northern 'stress zones' in the increase of southern species (e.g. foxes) which are adapted to warmer conditions and the decline in species (like the Arctic fox) which are adapted to cold conditions but which do not survive competition from other species well. Before the advent of fossil fuels the tree line was also often the limit of fixed human settlement, beyond which it was impossible to live all year round. (Likewise, the culture of the Eskimos, or Inuit, was based the fat energy obtained from sea mammals.)

Organisms can adapt to extremely cold conditions in many ways. Like the reindeer and their herders, most birds migrate to more clement areas for the winter. By sensibly using the resources afforded by the seasons and moving accordingly, the maximum benefit is obtained from the unproductive nature of the north, and it is allowed time to regenerate. The ending of the migration between summer and winter grazing grounds and instead remaining in a fairly limited area all year round has led to a deterioration of the winter pastures in particular and the need for 'emergency feeding' in winter. Because the fodder comes mainly from outside the reindeer husbandry region, reindeer herding is no longer an ecological economic activity whose development is dependent on the ability of the environment to support it. Particularly in the northernmost reindeer grazing associations, the scarcity of lichen has become an inhibiting factor in reindeer husbandry. Changes in the culture of reindeer herding are inevitably reflected in Saami culture.

Snow (muohta) is one of the characteristic features of Lapland. It is both beneficial and detrimental to nature. For example, it breaks tree branches and trunks and impedes the movement and feeding of animals. Among the very few vertebrate species living on the snow on the open fells all year round are the ptarmigan, the gyrfalcon, the raven and the Arctic fox.Apart from the ptarmigan they are all carnivores. Smaller animals survive the winter only by obtaining warmth and protection from the wind under the snow.With the snow several metres deep, the temperature at ground level remains around freezing point even in the coldest of air temperatures, which permits small rodents to reproduce in winter too. Gallinaceous birds and even small birds spend the depth of winter enveloped in the snow. The body temperature of titmice may drop by as much as ten degrees Centigrade during the night, which is a most effective way of conserving energy. Just as in buildings, dropping the temperature of the body saves heating costs. Another way of saving energy is to increase insulation. For example, the winter coat of the mountain hare has 700 hairs per square centimetre as compared with 200 300 in the summer coat. Naturally, insulation alone is not enough; fuel is also needed. Many animals ensure their supplies of fuel by hoarding food for the winter.

In the immediate vicinity of the tree line there is more life in winter too, and the range of species hardly differs from that of the adjoining forests. There we can find birds such as the willow grouse, the willow tit and the Siberian tit; and animals like the hare, the stoat and the weasel. It is not so much the cold as the lack of food that is an obstacle to animals' survival in the Arctic winter. If there is a good harvest of mountain birch seeds, flocks of hundreds of mealy redpoll, which normally migrate at least to southern Finland, may spend the winter as far north as the tree line.

</div>

<p>Denna språkversion existerar inte ännu